Recommendations

Meditation: how to become your own best friend

by Joy Ansaldo, neuropsychologist, and Sabine Aubril and Adrien Chauvet, nurses at UPPM La Roseraie.

Meditation was initially an ancestral spiritual practice associated with religion, and inevitably evokes images of monks in their orange robes sitting cross-legged in their temples bathed in incense. In recent years, however, interest in meditation has been growing and has transcended both geographical and phenomenological boundaries.

The recent events of the pandemic have prompted us to note that our reality is changing, impermanent, unstable. In the panic, we tend to want to find external solutions to bring us comfort: things like alcohol, drugs, sport, tobacco, food, screens, etc. It is no wonder that rates of depression and addiction have risen, leading to an increase in the use of anxiety medication, hypnotics and anti-depressants, as shown by the CoviPrev study (1) and the Epi-Phare report (2). These events have also highlighted our most basic psychological needs, and we can see that societal challenges are changing, that wellbeing and mental health are coming to the fore.

The purpose of meditation is to develop and encourage internal resources and skills to help better understand the events that we may need to face. As the world changes, we should learn to be more flexible, to accept change and live with it, as in Jean de La Fontaine’s fable The Oak and the Reed.

In practice, this involves bringing our attention to something in particular, such as our breath, one of our five senses, our body or even our emotions. Baer et al. (3) believe that there are five facets to mindfulness:

- Observing what is happening inside us, our thoughts (positive or negative), our emotions and our feelings (pleasant or unpleasant), but also what is going on in our environment, without looking for meaning and without judgement;

- Describing our thoughts, our emotions and our feelings using words;

- Not reacting to our inner experiences; in other words, not allowing ourselves to be overwhelmed by emotions, feelings and thoughts, learning to let go and be less impulsive;

- Not judging others, ourselves or situations, discerning facts (neutral and verifiable) from opinions (unique to each individual), being more tolerant;

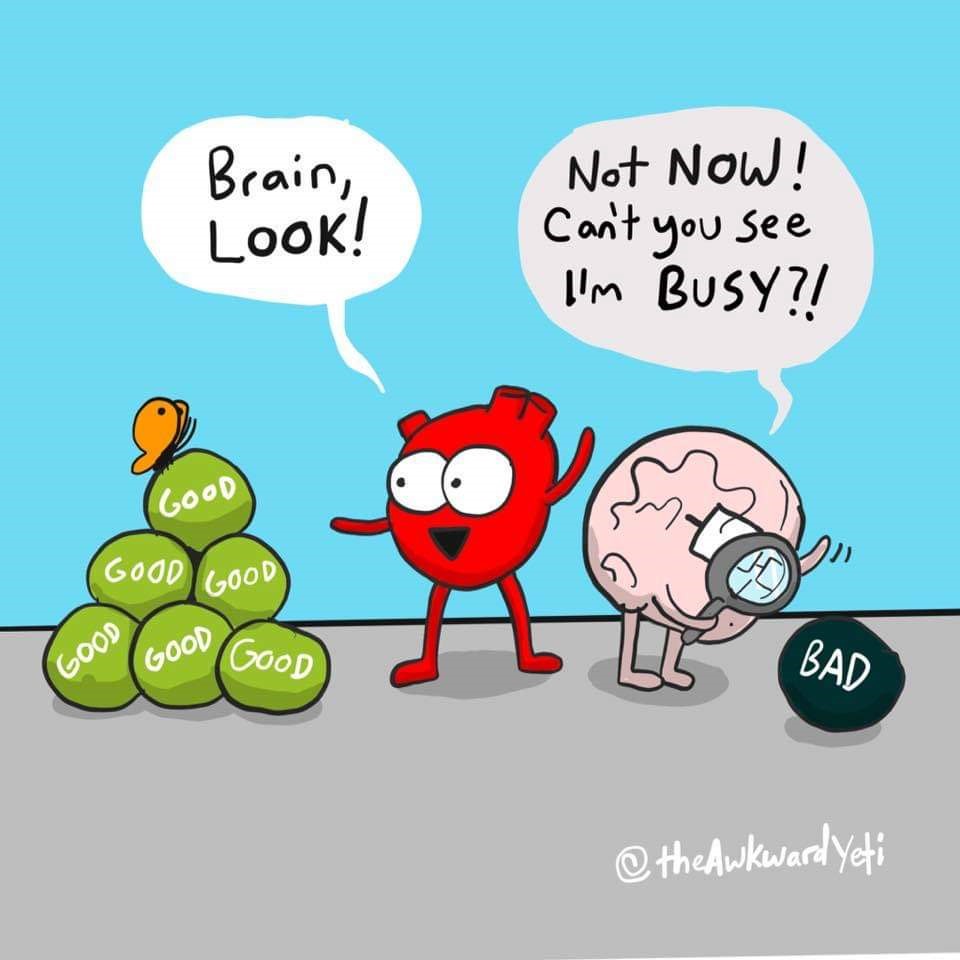

- Acting with awareness, doing one thing at a time, concentrating on the present moment rather than dwelling on the past or looking to the future, being grateful for what we have rather than focusing on what we want.

So it is truly about changing our mindset through a formal, regular practice, but also through an informal practice that is part of our daily habits.

Meditation has a number of benefits: (4, 5, 6)

- Reduced anxiety and improved sleep quality

- Reduction and prevention of relapse into depression

- Biological benefits for the brain and immune system (quicker production of antibodies)

- Reduced pain symptoms (particularly chronic pain)

- Reduction in problematic food behaviours (anorexia, bulimia, overeating)

- Reduction and prevention of relapse into addiction

- Improved attention and concentration, particularly in the context of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

In addition, the activation of the part of the brain involved in meditation can be visually observed using an electroencephalogram (EEG), which provides evidence of the direct effects on neuroplasticity. (7) In recent years, mindfulness meditation has attracted the interest of an increasing number of researchers and scientists, who are carrying out studies to demonstrate the effects of this practice. Jon Kabat-Zinn, a professor emeritus of medicine in the United States, is among the leading contributors promoting meditation within the field of medicine.

These days, meditation is used for a variety of different groups, including children, teenagers, adults, the elderly and patients with stabilised psychiatric conditions. It is increasingly becoming a part of healthcare professionals’ practice, as at the Psychiatry and Medical Psychology Unit (UPPM), where it has been adapted to the unit’s patients and the type of care provided.

For more information, please contact La Roseraie Psychiatry and Medical Psychology Unit on +377 98 98 44 20 (7 bis Avenue des Ligures, 98000 Monaco).

Sources :

- CoviPrev (2021). Une enquête pour suivre l’évolution des comportements et de la santé mentale pendant l’épidémie de COVID-19 https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/etudes-et-enquetes/coviprev-une-enquete-pour-suivre-l-evolution-des-comportements-et-de-la-sante-mentale-pendant-l-epidemie-de-covid-19#block-252159

- EPI-PHARE (2021). Rapport 6 : point de situation au 25 avril 2021 https://www.epi-phare.fr/rapports-detudes-et-publications/covid-19-usage-des-medicaments-rapport-6/

- Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using Self-Report Assessment Methods to Explore Facets of Mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45.

- Berghmans, C., Tarquinio, C., & Strub, L. (2010). Méditation de pleine conscience et psychothérapie dans la prise en charge de la santé et de la maladie. Santé mentale au Québec, 35(1), 49-83.

- Sampaio, C. V. S., Magnavita, G., & Ladeia, A. M. (2021). Effect of Healing Meditation on stress and eating behavior in overweight and obese women: A randomized clinical trial. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 45, 101468.

- Lenoir, A., & Eeckhout, C. (2020) L'effet de la méditation pleine conscience sur le bien-être des enfants et adolescent(e)s souffrant du trouble du déficit de l'attention avec hyperactivité (TDAH): Une revue de la littérature. Faculté des sciences de la motricité, Université catholique de Louvain.

- Matiz, A., Crescentini, C., Bergamasco, M., Budai, R., & Fabbro, F. (2021). Inter-brain co-activations during mindfulness meditation. Implications for devotional and clinical settings. Consciousness and Cognition, 95, 103210.

Illustration : https://theawkwardyeti.com/